Departures, arrests and fighting

In a world at war, there was no way these young people were going to remain passive. Moreover, everything about their environment helped to keep them geared up for action.

In June 1941, and every year from then on, many pupils seized the various opportunities that came their way to leave via Spain for Great Britain, considered to be the country in which the war against the Nazis was being fought. The youngest of them was caught on the buffers of a train heading south and brought back to the school. He was only twelve years old!

Some of them spent time in the Miranda del Ebro internment camp and prison before being able to continue along their way. Dozens were intercepted and interned or deported to Buchenwald, Mauthausen and Ravensbrück…

Others managed to reach Gibraltar and at last join the Polish Forces (army, air force and navy) in Great Britain. In 1944, those who joined the ranks of the 1st Polish Tank Regiment helped to liberate France. They fought in Normandy, Falaise, Chambois and Abbeville, and then in Belgium and Holland. Those who joined the 2nd Polish Corps under the command of General Anders fought in Italy.

Others enrolled at different universities. Many of them joined the Resistance movement, especially networks such as the POWN. This “Polish Organisation for Fighting for Independence” was led by the Polish government in exile from London. Zygmunt Lubicz-Zaleski and Wenceslas Godlewski themselves maintained links with the French and Polish resistance armies.

A turning point came when the German army moved into the ‘zone libre’, the unoccupied area of southern France. Up until then, the school had been looked upon kindly by French officials, including several senior civil servants, and been actively helped by them. In the eyes of the occupier however, it became an object of suspicion.

The Prefecture ruled that no pupil over the age of seventeen could be admitted to the school, which meant that it could no longer accept any former soldiers who might join the Resistance in France or abroad.

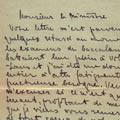

In March 1943, for the first time, the school was hit by the arrest of its headmaster, Professor Lubicz-Zaleski. He was sent to Milan by the Italian police, tortured, handed over to the Gestapo and then deported to Buchenwald. Professor Godlewski took over as headmaster, but a year later, he too was arrested by the Gestapo while taking part in a meeting of the GAPF to organise departures to Spain. He was deported to Mauthausen from which he returned a broken man.

Marcel Malbos was also arrested but by a lucky coincidence released again the same day.

The summer of 1944 arrived. The Vercors region had been turned into a fortress defended by some five thousand French Resistance fighters. From the start of the year, the Germans had tried in vain to crush the resistance put up by this stronghold. On 13 June, they mounted a failed attack against St-Nizier, but then on 15 June launched a fresh, and this time successful, attack. They burned the village to the ground, although they did not advance any further.

July came, and a good many pupils did not go home for the holidays… A general mobilisation was ordered... Some thirty pupils and teachers enlisted in the FFI (French Forces of the Interior). None of them had any military experience or training.

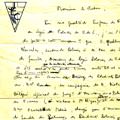

Jerzy Delingier, one of these pupils, wrote the following to his mother, “I’ve passed my Bac, which for me, symbolises a sort of pass for life. Lessons have ended but work in the fields is starting, and with that work, come huge changes in my life.”

For the older pupils, “change” meant leaving to join the combat units and, for the younger ones among them, fitting out an aerodrome in Vassieux-en-Vercors.

On 20 July, the Germans launched their attack.

On 21 July, all hell broke loose in Vassieux, when instead of the Allied reinforcements that were expected, twenty German gliders packed with paratroopers landed. The result was a massacre… a dozen Poles died that day and in the days that followed, including Jerzy Delingier. The survivors hid in the forests before joining other groups of partisans.

Professors Harwas and Gerahrd took part in the fighting, but were arrested, taken to Lyon and shot the day before the city was liberated.

As one of the monuments commemorating the days of glory and drama in the Vercors proclaims, “The blood will never dry on this land”.

Elsewhere, the fighting continued.

Ultimately, twenty-four teachers, pupils and staff members from the Polish High School were to pay for their commitment with their lives. Another thirty were deported, two of whom never returned.

In Villard, the 7th Station of the Valchevrière Way of the Cross is different to all the others. Built just after the war and known as the “Poles’ Station”, it is based on the style of the chapels in Zakopane and bears the following words, “The teachers, pupils and employees of the Cyprian Norwid Polish High School suffered in prisons and in concentration camps, and gave their lives for freedom, justice and human dignity, for Poland and for France.”

In the graveyard in Villard, a single vault is the last resting place of six Poles who died fighting for freedom, and of Wenceslas Godlewski, who died in 1996.

The coffins of other pupils and teachers have been transferred to the La Doua National Graveyard on the outskirts of Lyon.